Intro to Graphix

Graphix is a programming language using the dataflow paradigm. It is particularly well suited to building user interfaces, and interacting with resources in netidx. Dataflow languages like Graphix are “reactive”, like React or Vue, except at the language level instead of just as a library. A Graphix program is compiled to a directed graph, operations (such as +) are graph nodes, edges represent paths data can take through the program. A simple expression like,

2 + 2

will compile to a graph like

const(2) ──> + <── const(2)

The semantics of simple examples like this aren’t noticibly different from a normal programming language. However a more complex example such as,

let x = cast<i64>(net::subscribe("/foo")?)?;

print(x * 10)

compiles to a graph like

const(10)

│

│

▼

const("/foo") ──> net::subscribe ──> cast<i64> ──> * ──> print

Unlike the first example, the value of net::subscribe isn’t a

constant, it can change if the value published in netidx changes. If

that happens the new value will flow through the graph and will be

printed again. If the published value of “/foo” is initially 10, and

then the value of “/foo” changes to 5 then the program will print.

100

50

It will keep running forever, if “/foo” changes again, it will print more output. This is a powerful way to think about programming, and it’s especially well suited to building user interfaces and transforming data streams.

Dataflow but Otherwise Normal

Besides being a dataflow language Graphix tries hard to be a normal functional language that would feel familiar to anyone who knows Haskell, OCaml, F# or a similar ML derived language. Some of it’s features are,

- lexically scoped

- expression oriented

- strongly statically typed

- type inference

- structural type discipline with nomial abstract types

- parametric polymorphism

- algebraic data types

- pattern matching

- first class functions, and closures

- late binding

Installing Graphix

To install the Graphix shell from source you need to install a rust build environment. See here for instructions on how to do that for your platform. Once you have that set up, you can just run

cargo install graphix-shell

That should build the graphix command and install it in your

~/.cargo/bin directory. Windows and Mac OS should work out of the box

as long as you have the prerequisites for rust installed.

Linux Prerequisites

Debian/Ubuntu

You need to install

- clang

- libkrb5-dev

On Fedora

You need to install

- clang-devel

- krb5-devel

Netidx

Graphix uses netidx to import and export data streams. Netidx works with zero configuration for local use on a single machine - separate Graphix processes can communicate with each other out of the box.

For more advanced setups involving multiple machines, authentication, or custom resolver configurations, see the netidx book for details on setting up a netidx environment.

Getting Started

Welcome to Graphix! This tutorial will get you up and running in about 10-15 minutes. You’ll learn how to use the interactive REPL, write your first expressions, and create a simple reactive program.

By the end of this guide, you’ll understand the basics of Graphix’s reactive dataflow model and be ready to explore the language in depth.

Prerequisites

Make sure you’ve already installed Graphix. You can verify your installation by running:

graphix --version

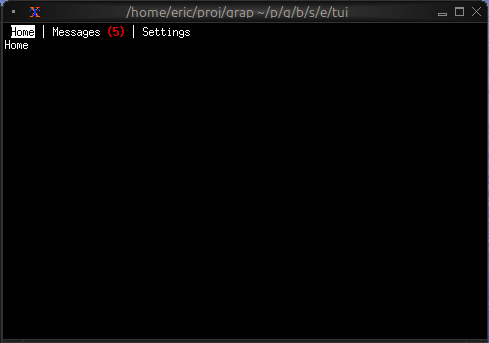

Starting the REPL

The Graphix shell provides an interactive Read-Eval-Print Loop (REPL) where you can experiment with the language. Start it by running graphix with no arguments:

graphix

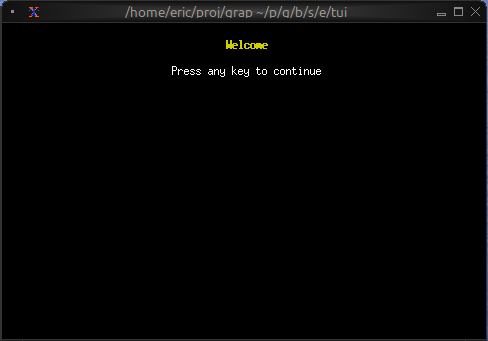

You’ll see a prompt that looks like this:

Welcome to the graphix shell

Press ctrl-c to cancel, ctrl-d to exit, and tab for help

〉

The REPL evaluates expressions and shows you both the type and the value. The output format is:

-: Type

value

Let’s try it!

Your First Expressions

Arithmetic

Type some simple arithmetic at the prompt:

〉2 + 2

-: i64

4

The -: i64 line tells you the result is a 64-bit integer, and 4 is

the value. You may be wondering why you don’t get the 〉 prompt after

running this expression. This is because, being a dataflow language,

expressions are pipelines that can output more than one value, they

will run until you stop them by hitting ctrl-c. Do this now to get the

prompt back.

Since ctrl-c is used to stop the currently running pipeline, if you want to exit the REPL press ctrl-d.

Try a more complex expression:

〉10 * 5 + 3

-: i64

53

〉2.5 * 4.0

-: f64

10.0

Notice that integer arithmetic produces i64 (integer) results, while floating-point arithmetic produces f64 (float) results.

Strings

Strings are written in double quotes:

〉"Hello, Graphix!"

-: string

"Hello, Graphix!"

String Interpolation

Graphix supports string interpolation using square brackets. Any expression inside [...] in a string will be evaluated and inserted:

〉"The answer is [2 + 2]"

-: string

"The answer is 4"

〉"2 + 2 = [2 + 2], and 10 * 5 = [10 * 5]"

-: string

"2 + 2 = 4, and 10 * 5 = 50"

This is incredibly useful for building dynamic strings!

Variables with Let Binds

Use let to create named bindings:

〉let x = 42

〉x

-: i64

42

〉let name = "World"

〉"Hello, [name]!"

-: string

"Hello, World!"

You can reuse the same name to create a new binding (this is called shadowing):

〉let x = 10

〉let x = x + 5

〉x

-: i64

15

The second let x creates a new binding that references the previous value of x.

Functions

Functions in Graphix are first-class values. Create them with the lambda syntax |args| body:

〉let double = |x| x * 2

〉double(21)

-: i64

42

You can add type annotations if you want to be explicit:

〉let add = |x: i64, y: i64| x + y

〉add(10, 32)

-: i64

42

Functions can capture variables from their surrounding scope:

〉let multiplier = 3

〉let times_three = |x| x * multiplier

〉times_three(14)

-: i64

42

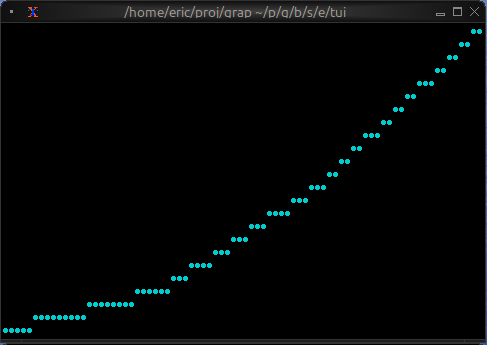

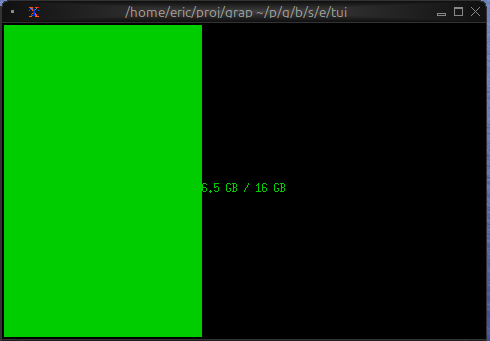

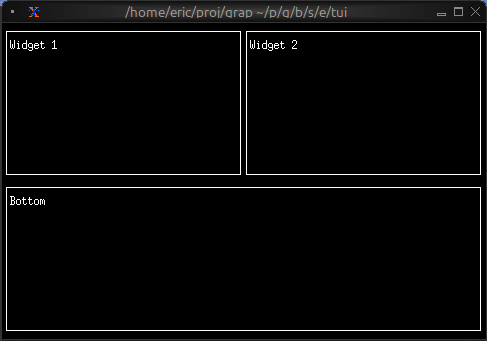

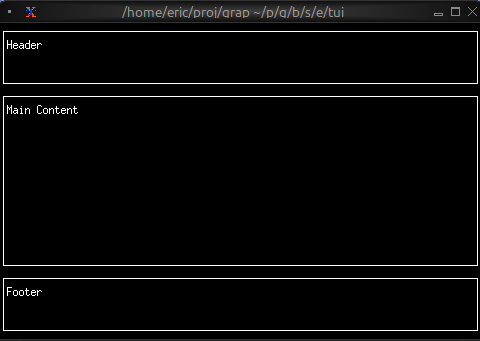

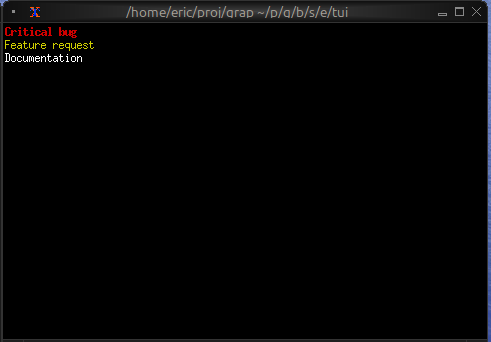

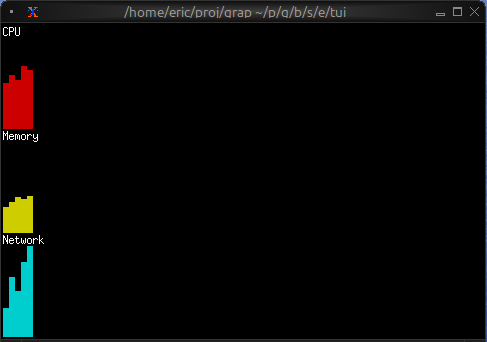

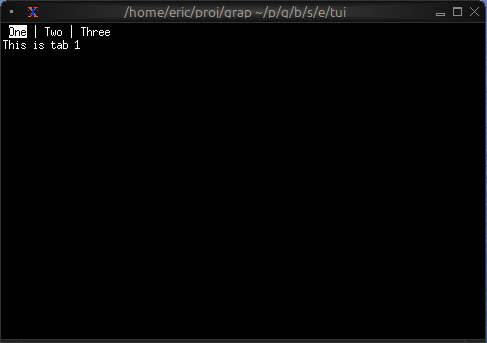

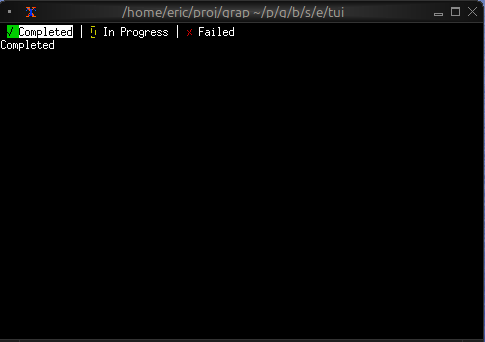

Creating Your First File

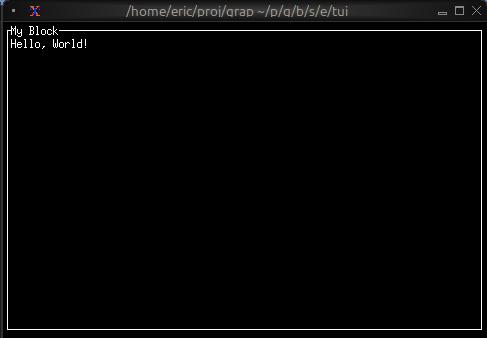

Now let’s write a real Graphix program! Create a file called hello.gx with this content:

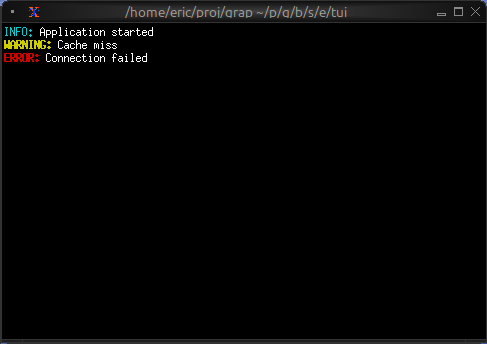

use tui;

use tui::text;

let count = 0;

let timer = time::timer(duration:1.s, true);

count <- timer ~ (count + 1);

text(&"Count: [count]")

This program demonstrates Graphix’s reactive nature:

- We start with

count = 0 time::timer(duration:1.s, true)creates a timer that fires every second- The

~operator samples the right side when the left side updates count <- ...schedules an update tocountfor the next cycle- Every second,

countincrements and the text automatically updates - The last expression creates a text widget displaying the count

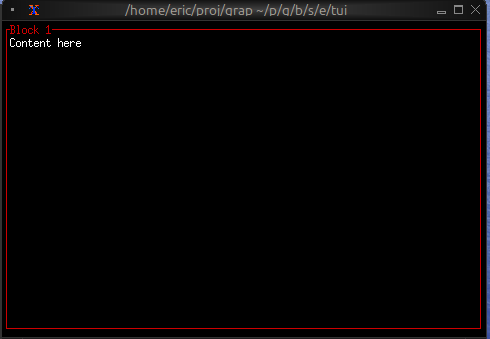

Running Your File

Run your program with:

graphix hello.gx

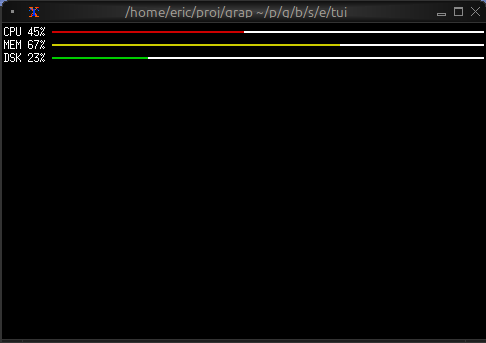

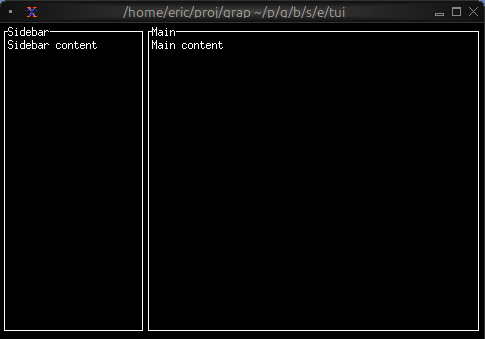

You’ll see a terminal UI that displays the count increasing every second! The screen updates automatically because Graphix tracks dependencies and propagates changes through the dataflow graph.

To stop the program, press Ctrl+C.

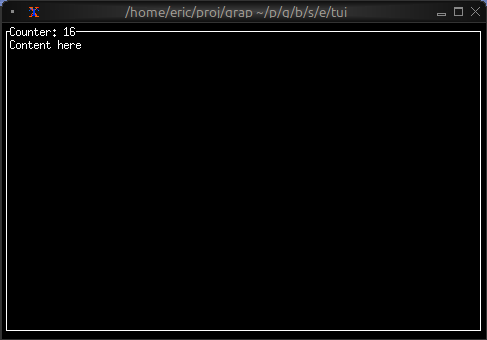

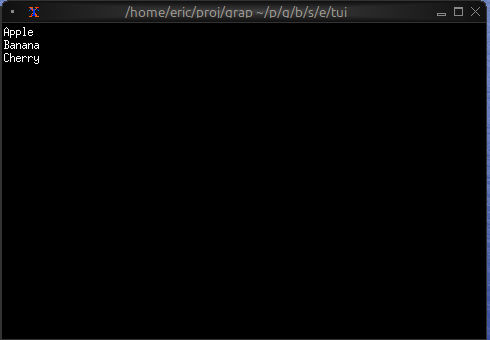

A Simpler Example

If you want to see the reactive behavior without the TUI, try this simpler version (counter.gx):

let count = 0;

let timer = time::timer(duration:1.s, true);

count <- timer ~ (count + 1);

"Count: [count]"

Run it with graphix counter.gx and you’ll see the count printed to the console every second.

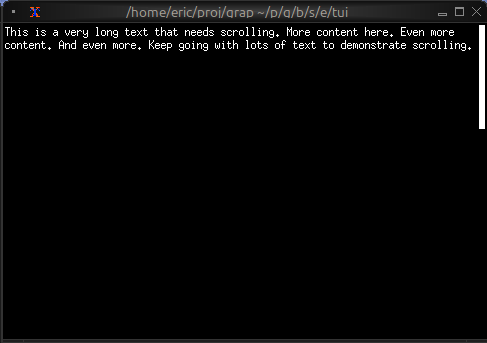

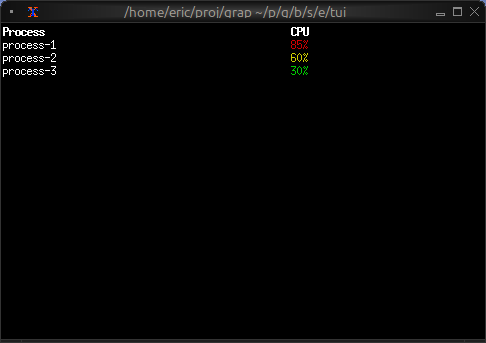

Understanding the Output

In Graphix programs:

- The last value is what determines what the shell displays

- If it’s a

Tuitype (like our text example), then it is rendered as a TUI - Otherwise, the value is printed to the console every time it updates

- If it’s a

- Use

printorprintlnfor explicit output during execution - Programs run forever unless they explicitly exit - they’re reactive graphs that respond to events

The Dataflow Model

The key insight: when timer updates, it triggers an update to count (via the <- connect operator), which triggers an update to the text widget. The entire chain reacts automatically. You describe what should happen, not when or how to update things.

This is very different from traditional imperative programming where you’d need loops and manual state management. In Graphix, you build a graph of dependencies and the runtime handles updates for you.

Try It Yourself

Experiment with these ideas:

- Modify the counter to count down instead of up

- Make it count by 2s or 10s instead of 1s

- Change the timer interval to 0.5 seconds

- Display multiple values that update independently

- Try arithmetic on the count (show doubled value, squared value, etc.)

Next Steps

Now that you’ve experienced Graphix’s reactive nature, you’re ready to dive deeper:

- Core Language - Learn the fundamental language constructs

- Functions - Master functions, closures, and higher-order programming

- Building UIs - Create rich terminal user interfaces

- Standard Library - Explore built-in functions and modules

The best way to learn Graphix is to experiment! Keep the REPL open as you read through the documentation and try out the examples. Every code snippet in this book is designed to be runnable.

Core Language

This chapter introduces the core constructs that make Graphix work. If you’re coming from imperative languages like Python, Java, or C, some of these concepts will feel familiar—but the reactive twist makes them work differently than you might expect.

Types: Strong but Flexible

Graphix has a powerful static type system, but you’ll rarely write type annotations. The compiler infers types for you using structural typing—types are compared by their shape, not their name. A struct {x: i64, y: i64} is the same type whether you call it Point or Vector or don’t name it at all.

The Fundamental Types section covers the built-in numeric types (i64, f64, u32, etc.), booleans, strings, durations, and more. You’ll learn how arithmetic works across different numeric types, how string interpolation works with [...] brackets, and why division by zero doesn’t crash your program.

Reading Type Signatures teaches you how to read the type annotations you’ll see throughout the documentation. Function types like fn(Array<'a>, fn('a) -> 'b) -> Array<'b> tell you exactly what a function expects and returns, including what errors it might throw.

Binding Values and Building Blocks

In Graphix, you create bindings with let. Unlike variables in other languages, these bindings can update over time—they’re more like pipes that different values flow through.

Let Binds explains how to create bindings, how shadowing works, and why every binding in Graphix is potentially reactive. When you write let x = 42, you’re not just storing a value—you’re creating a node in the dataflow graph.

Blocks shows how to group expressions with {...} to create scopes, hide intermediate bindings, and build up complex expressions. Blocks are expressions too—they evaluate to their last value.

Use lets you bring module names into scope so you can write map(arr, f) instead of array::map(arr, f). Simple, but essential as your programs grow.

Connect: The Heart of Reactivity

This is where Graphix becomes special. The <- operator (connect) is the only way to create cycles in your dataflow graph, and it’s the key to writing reactive programs and loops.

Connect is the most important section in this chapter. When you write:

let count = 0;

count <- timer ~ (count + 1)

You’re telling Graphix: “When timer updates, increment count for the next cycle.” Connect schedules updates for the future, which is how you build everything from simple counters to complex state machines. It’s also the only looping construct in Graphix—there’s no for or while, just connect and select working together.

Select: Powerful Pattern Matching

The select expression is Graphix’s answer to switch, match, and if/else. It lets you match on types, destructure complex data, and ensure at compile time that you’ve handled every case.

Select shows you how to:

- Match on union types and ensure you handle all variants

- Destructure arrays with slice patterns like

[head, tail..] - Match structs with patterns like

{x, y} - Guard patterns with conditions like

n if n > 10 - Build loops by combining select with connect

The compiler checks your select expressions exhaustively—if you forget a case, it won’t compile. If you match a case that can never happen, it won’t compile. This eliminates entire classes of bugs.

Error Handling: Exceptions, Done Right

Graphix has first-class error handling with try/catch and the ? operator. Errors are just values with the special Error<'a> type, and they’re tracked through the type system.

Error Handling explains:

- How

?throws errors to the nearest try/catch in dynamic scope - How error types are checked at compile time—you can’t forget to handle an error type

- How the

$operator silently swallows errors (use with caution!) - How error chains track the full context of where errors originated

Every error that gets raised with ? is wrapped in an ErrChain that captures the file, line, column, and full stack of previous errors. No more mystery exceptions.

How It All Fits Together

These constructs combine to create the Graphix programming model:

- You create bindings that hold values

- You build expressions that compute new values from old ones

- You use select to handle different cases and make decisions

- You use connect to update bindings when events occur

- The type system ensures everything is safe and correct

- Errors propagate cleanly through try/catch

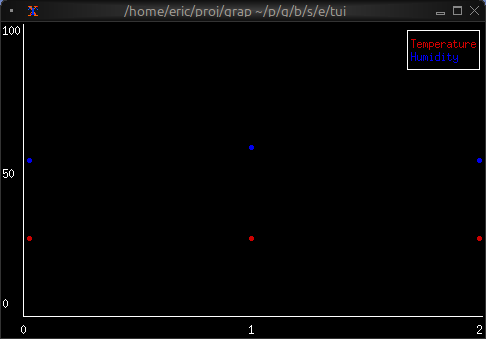

The result is a language where you describe relationships between values, and the runtime automatically maintains those relationships as things change. A temperature value updates, and the Fahrenheit conversion updates automatically. A timer fires, and your counter increments. A network subscription delivers new data, and your UI reflects it instantly.

Fundamental Types

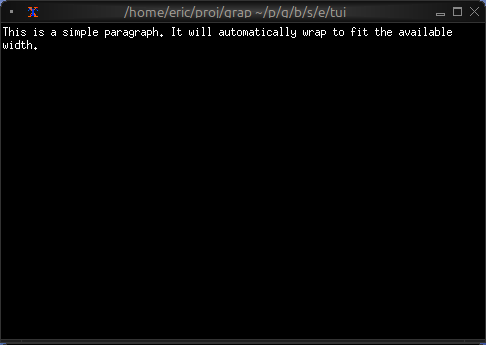

Graphix has a few fundamental data types, the Graphix shell is a good way to

explore them by trying out small Graphix expressions. You can run the Graphix

shell by invoking graphix with no arguments.

Numbers

i32, u32, i64, u64, f32, f64, and decimal are the fundamental

numeric types in Graphix. Literals are written with their type prefixed, except

for i64 and f64 which are written bare. for example, u32:3 is a u32

literal value.

decimal is an exact decimal representation for performing financial

calculations without rounding or floating point approximation errors.

The basic arithmetic operations are implemented on all the number types with all the other number types.

| Operation | Operator |

|---|---|

| Add | + |

| Subtract | - |

| Multiply | * |

| Divide | / |

| Mod | % |

The compiler will let you do arithmetic on different types of numbers directly without casting, however the return type of the operation will be the set of all the types in the operation, representing that either type could be returned. If you try to pass this result to a function that wants a specific numeric type, it will fail at compile time.

〉1. + 1

-: [i64, f64]

2

〉let f = |x: i64| x * 10

〉f(1. + 1)

error: in expr

Caused by:

0: at: line: 1, column: 3, in: (f64:1. + i64:1)

1: at: line: 1, column: 3, in: (f64:1. + i64:1)

2: type mismatch '_1046: i64 does not contain [i64, f64]

Division by zero raises an error to the nearest error handler (see Error Handling). If unhandled, it will be printed to stderr by the shell.

〉0 / 0

-: i64

unhandled error: error:"in expr at line: 1, column: 1 attempt to divide by zero"

The result type of the division is still i64, but the actual value is an error. You can handle division by zero using the ? or ` operators:

〉(0 / 0)?

-: Result<i64, Error<`ArithError(string)>>

error:["ArithError", "in expr at line: 1, column: 2 attempt to divide by zero"]

If division by zero occurs and is not handled, the expression will not update until the divisor changes to a non-zero value. This can cause issues if your program depends on continuous updates from that expression.

Overflow and underflow are handled by wrapping:

〉u32:0 - u32:1

-: u32

4294967295

v32, z32, v64, z64

These number types are the same as the normal types except when they are sent over the wire via netidx (or written to a file) they use variable width encoding instead of normal encoding. The number of bytes used varies for 64 bit numbers to between 1 and 10. Small numbers (below 127) are encoded in 1 byte, larger number use more bytes. The type correspondence is,

| Compact | Normal |

|---|---|

| v32 | u32 |

| z32 | i32 |

| v64 | u64 |

| z64 | i64 |

Number Sets

There are a few sets of number types that classify numbers into various kinds.

Number being the most broad, it contains all the number types. Int contains

only integers, Real contains only reals (decimal plus the two float types),

SInt contains signed integers, UInt contains unsigned integers.

Bool

Boolean literals are written as true and false, and the name of the boolean

type is bool.

Boolean expressions using &&, ||, and ! are supported. These operators

only operate on bool. They can be grouped with parenthesis. For example,

〉true && false

-: bool

false

〉true || false

-: bool

true

〉!true

-: bool

false

〉!1

error: in expr

Caused by:

0: at: line: 1, column: 2, in: i64:1

1: type mismatch bool does not contain i64

Duration

A time duration. The type name is duration, and the literals are written as,

duration:1.0s, duration:1.0ms, duration:1.0us, duration:1.0ns. Durations

can be added, and can be multiplied and divided by scalars.

〉duration:1.0s + duration:1.0s

-: duration

2.s

〉duration:1.0s * 50

-: duration

50.s

〉duration:1.0s / 50

-: duration

0.02s

DateTime

A date and time in the UTC time zone. The type name is datetime and literals

are written in RFC3339 format inside quotes. For example,

datetime:"2020-01-01T00:00:00Z". You can add and subtract duration from

datetime.

〉datetime:"2020-01-01T00:00:00Z" + duration:30.s

-: datetime

2020-01-01 00:00:30 UTC

You can enter datetime literals in local time and they will be converted to UTC. For example,

〉datetime:"2020-01-01T00:00:00-04:00"

-: datetime

2020-01-01 04:00:00 UTC

String

Strings in Graphix are UTF8 encoded text. The type name is string and the

literal is written in quotes "this is a string". C style escape sequences are

supported, "this is \" a string with a quote and a \n". Non printable

characters such as newline will be escaped by default when strings are printed

to the console, you can use print to print the raw string including control

characters.

String Interpolation

String literals can contain expressions that will be evaluated and joined to the string,

such expressions are surrounded by unescaped [] in the string. For example,

〉let row = 1

〉let column = 999

〉"/foo/bar/[row]/[column]"

-: string

"/foo/bar/1/999"

Values in an interpolation need not be strings, they will be cast to a string

when they are used. You can write a literal [ or ] in a string by escaping

it.

〉"this is a string with a \[ and a \] but it isn't an interpolation"

-: string

"this is a string with a [ and a ] but it isn't an interpolation"

Any

The Any type is a type that unifies with any other type, it corresponds to the

underlying variant type that represents all values in Graphix (and netidx). It

is not used very often, as it provides very few guarantees, however it has it’s

place. For example, Any is the type returned by net::subscribe, indicating

that any valid netidx value can come from the network. Usually the first thing

you do with an Any type is call cast to turn it into the type you expect (or

an error), or use a select expression to match it’s type (more on select later).

Null

Null is nothing, just like in many other languages. Unlike most other languages

null is a type not a catch all. If the type of a value does not include null

then it can’t be null. The set ['a, null] (alias Option<'a>) is commonly

used to represent things that will sometimes return null.

Array

Arrays are immutable, contiguous, and homogeneous. They are

parameterized, Array<string> indicates an array of strings. Arrays

are zero indexed a[0] is the first element. Array elements can be

any type, including other arrays at arbitrary levels of nesting. There

is a special array type that acts like Array<Any>, that represents

the fundamental array type in the underlying value representation.

Array literals are written like [x, y, z]. There are many functions

in the array module of the standard library for working with arrays.

Array Slicing and Indexing

Graphix supports array subslicing, the syntax will be familiar to Rust programmers.

a[2..]a slice from index 2 to the end of the arraya[..4]a slice from the beginning of the array to index 3a[1..3]a slice from index 1 to index 2a[-1]the last element in the arraya[-2]the second to last element in the array

..= is not supported however, the second part of the slice will always be the

exclusive bound. Literal numbers can always be replaced with a Graphix

expression, e.g. a[i..j] is perfectly valid.

Mutability and Implementation

Arrays are not mutable, like all other Graphix values. All operations that “change” an array, actually create a new array leaving the old one unchanged. This is even true of the connect operator, which we will talk more about later.

There are a couple of important notes to understand about the implementation of Arrays.

-

Arrays are memory pooled, in almost all cases (besides really huge arrays) creating an array does not actually allocate any memory, it just reuses a previously used array that has since become unused. This makes using arrays a lot more efficient than you might expect.

-

Arrays are contiguous in memory. This means they are generally very memory efficient, each element is 2 machine words, and O(1) to access. However there are a few cases where this causes a problem, such as building up an array by appending one element at a time. This is sadly an O(n^2) operation on arrays. You may wish to use another data structure, such as a map (which would be O(n log(n)) if you need to build a large data structure this way.

-

Array slices are zero copy, and also pooled. They simply create a light weight view into the array. This means algorithms that progressively deconstruct an array by slicing are O(N) not O(N^2) and the constants are very fast.

Tuples

Tuples are written (x, y), they can be of arbitrary length, and each element

may have a different type. Tuples may be indexed using numeric field indexes.

Consider

let x = (1, 2, 3, 4);

x.0

Will print 1.

Map

Maps in Graphix are key-value data structures with O(log(N)) lookup, insert, and

remove operations. Maps are parameterized by their key and value type, for

example Map<string, i64> indicates a map with string keys and integer values.

There are many functions for working with maps in the map standard library

module

Map Literals

Maps can be constructed using the {key => value} syntax:

〉{"a" => 1, "b" => 2, "c" => 3}

-: Map<'_1893: string, '_1895: i64>

{"a" => 1, "b" => 2, "c" => 3}

Keys and values can be any Graphix type, for example here is a map where the key

is a Map<string, i64>.

{{"foo" => 42} => "foo", {"bar" => 42} => "bar"}

-: Map<'_1919: Map<'_1915: string, '_1917: i64>, '_1921: string>

{{"bar" => 42} => "bar", {"foo" => 42} => "foo"}

Map Indexing

Maps can be indexed using the map{key} syntax to retrieve values:

〉let m = {"a" => 1, "b" => 2, "c" => 3}

〉m{"b"}

-: ['_1907: i64, Error<`MapKeyError(string)>]

2

If a key is not present in the map, indexing returns a MapKeyError:

〉m{"missing"}

-: ['_1907: i64, Error<`MapKeyError(string)>]

error:["MapKeyError", "map key \"missing\" not found"]

Mutability and Implementation

Like all Graphix values, maps are immutable. All operations that “change” a map actually create a new map, leaving the original unchanged. Maps are memory pooled and very efficient - creating new maps typically reuses existing memory rather than allocating new memory.

Maps maintain their key-value pairs in a balanced tree structure, ensuring O(log(N)) performance for all operations regardless of map size.

Error

Error is the built in error type. It carries a type parameter indicating the

type of error, for example Error<MapKeyError(string)>is an error that carries a ``MapKeyError `` variant. You can access the inner error value

using e.0 e.g.,

〉let e = error(`MapKeyError("no such key"))

〉e.0

-: `MapKeyError(string)

`MapKeyError("no such key")

More information about dealing with errors is available in the section on error handling.

Reading Type Signatures

Throughout this book and in the standard library documentation, you’ll encounter function type signatures. This guide will help you understand what they mean. Don’t try to memorize everything here - just use this as a reference when you encounter unfamiliar notation.

Basic Function Signatures

The simplest function signature looks like this:

val double: fn(i64) -> i64

This breaks down into:

fn(...)- this is a functioni64- takes one parameter of type i64 (64-bit integer)-> i64- returns a value of type i64

Another example:

val concat: fn(string, string) -> string

Takes two strings, returns a string.

Type Parameters (Generics)

Type parameters (like generics in other languages) are written with a single quote followed by an identifier: 'a, 'b, 'e, etc.

Simple Type Parameters

val identity: fn('a) -> 'a

This means: “takes a value of any type 'a and returns a value of the same type 'a”. The identity function could work with integers, strings, or any other type.

val first: fn(Array<'a>) -> 'a

This means: “takes an array of any type 'a and returns a single element of type 'a”. If you pass an Array<string>, you get back a string. If you pass an Array<i64>, you get back an i64.

Multiple Type Parameters

val map: fn(Array<'a>, fn('a) -> 'b) -> Array<'b>

This function takes:

- An array of type

'a - A function that transforms

'ainto'b - Returns an array of type

'b

The types 'a and 'b can be the same or different.

Optional Labeled Arguments

Arguments prefixed with ?# are optional and labeled:

val text: fn(?#style: Style, string) -> Widget

This function can be called in two ways:

text("Hello") // style uses default value

text(#style: my_style, "Hello") // style is specified

Order Flexibility

Labeled arguments can be provided in any order, but must come before positional arguments:

val widget: fn(?#width: i64, ?#height: i64, string) -> Widget

// All of these are valid:

widget("text")

widget(#width: 100, "text")

widget(#height: 50, #width: 100, "text")

widget(#height: 50, "text")

Required Labeled Arguments

Arguments with # but no ? are required but labeled:

val input_handler: fn(

#handle: fn(Event) -> Response,

&Widget

) -> Widget

You must provide #handle, but it doesn’t have to be in the first position. However, it must come before the unlabeled &Widget argument:

input_handler(#handle: my_handler, &my_widget)

Variadic Arguments

The @args notation means a function accepts any number of arguments:

val sum: fn(@args: i64) -> i64

You can call this with any number of integers:

sum(1, 2, 3)

sum(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10)

Variadic with Required Arguments

Sometimes a function requires at least one argument:

val max: fn('a, @args: 'a) -> 'a

The first 'a is required, then any number of additional arguments of the same type.

Reference Types

An ampersand & before a type means “reference to” rather than the value itself:

val text: fn(&string) -> Widget

This takes a reference to a string, not the string value directly. References are important for:

- Efficiency - avoid copying large data structures

- Reactivity - updating a referenced value triggers updates without rebuilding entire structures

Create a reference with & and dereference (get the value) with *:

let s = "Hello";

let r = &s; // r is a reference to s

let v = *r; // v is the value "Hello"

In function signatures, &T in a parameter position means the function expects a reference. In widget examples, you’ll often see:

block(#title: &line("My Title"), &my_widget)

The &line(...) creates a reference to the line, and &my_widget is a reference to the widget.

For a deeper dive, see References.

Error Types (throws)

When a function can throw errors, the signature includes throws:

val divide: fn(i64, i64) -> i64 throws `DivideByZero

This function returns i64 if successful, but might throw a DivideByZero error.

Multiple Error Types

A function can throw multiple error types:

val parse_and_divide: fn(string, string) -> i64 throws [`ParseError, `DivideByZero]

Generic Error Types

Often error types are parameterized:

val filter: fn('a, fn('a) -> bool throws 'e) -> 'a throws 'e

This means: the filter function itself doesn’t throw errors, but if the function you pass to it throws errors of type 'e, then filter will also throw those same errors.

Result Type

The Result type is a convenient way to represent success or error:

type Result<'r, 'e> = ['r, Error<'e>]

So a function signature like:

val parse: fn(string) -> Result<i64, `ParseError>

Returns either an i64 (success) or an Error<ParseError>` (failure).

See Error Handling for complete details on working with errors.

Set Types

Square brackets [...] denote a set type - the value can be any one of the types in the set:

val process: fn([i64, string]) -> string

This function accepts either an i64 or a string, and returns a string.

Optional Types (Nullable)

The pattern [T, null] means “T or nothing”:

val find: fn(Array<string>, string) -> [string, null]

Returns a string if found, null if not found. This is aliased as Option<T>:

type Option<'a> = ['a, null]

val find: fn(Array<string>, string) -> Option<string>

Nested Sets

Types can nest arbitrarily:

val sum: fn(@args: [Number, Array<[Number, Array<Number>]>]) -> Number

This accepts numbers, arrays of numbers, or even arrays of (numbers or arrays of numbers). The flexibility allows you to call:

sum(1, 2, 3)

sum([1, 2], [3, 4])

sum(1, [2, 3], 4)

Function Constraints

Type variables in functions can have constraints:

let sum<'a: Number>(@args: 'a) -> 'a

This is subtly different from the sum examples earlier. This says,

sum is a function that takes any number of arguments of the same

type and returns the same type, and that type must be some kind of

number.

Auto Parameters

The compiler often infers type variables (and constrains them) by itself during the type inference process.

if we compile a function with no type constraints, such as:

let f = |x, y| x + y

It’s type will be something like:

val f: fn<

'_2073: Error<ErrChain<`ArithError(string)>>,

'_2069: Number,

'_2067: Number,

'_2071: Number

>('_2067, '_2069) -> '_2071 throws '_2073

The compiler has inferred a bunch of properties here,

- both arguments must be of type

Number, that’s what the constraints on'_2067: Numberand_2069: Numbermean. - both arguments need not be the same type, hence they are different type variables

- the return type will also be a number, hence

'_2071: Number, but it may not be the same type of number as either of the arguments. - the function may throw an arithmetic exception, hence the constraint

on

'_2073

In the shell this rather imposing type signature is made even more

complex by the shell also telling you what type variables are

currently bound to, or unbound if they aren’t bound. So in the shell this pops out as,

〉f

-: fn<'_2073: unbound: Error<ErrChain<`ArithError(string)>>, '_2069: unbound: Number, '_2067: unbound: Number, '_2071: unbound: Number>('_2067: unbound, '_2069: unbound) -> '_2071: unbound throws '_2073: unbound

The constraint '_2069: unbound: Number is read as. _2069 is not

currently bound to a type but is constrained to type Number. This is

all useful information, even though it’s intimidating at first it’s

worth putting in the work to learn to decipher it.

Putting It All Together

Let’s decode some complex real-world signatures:

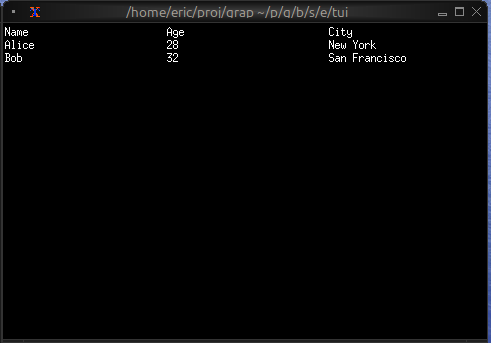

Example 1: TUI Table Widget

val table: fn(

?#header: &Row,

?#selected: &i64,

?#row_highlight_style: &Style,

?#highlight_symbol: &string,

&Array<&Row>

) -> Widget

Breaking it down:

?#header: &Row- optional labeled argument, reference to a Row?#selected: &i64- optional labeled argument, reference to selected index?#row_highlight_style: &Style- optional labeled argument, reference to a Style?#highlight_symbol: &string- optional labeled argument, reference to symbol string&Array<&Row>- required unlabeled argument, reference to array of row references-> Widget- returns a Widget

All parameters are references because the table needs to react to changes without rebuilding.

Example 2: Filter Function

val filter: fn('a, fn('a) -> bool throws 'e) -> 'a throws 'e

Breaking it down:

'a- a value of any typefn('a) -> bool throws 'e- a predicate function that:- Takes the same type

'a - Returns bool

- Might throw errors of type

'e

- Takes the same type

-> 'a- returns the same type as inputthrows 'e- propagates any errors from the predicate

Example 3: Queue Function

val queue: fn(#clock: Any, 'a) -> 'a

Breaking it down:

#clock: Any- required labeled argument of any type, just used as an event source'a- a value of any type-> 'a- returns values of the same type

Call it like: queue(#clock: my_timer, my_value)

Example 4: Array Map

val map: fn(Array<'a>, fn('a) -> 'b throws 'e) -> Array<'b> throws 'e

Breaking it down:

Array<'a>- array of any type'afn('a) -> 'b throws 'e- transformation function that:- Takes type

'a(array element type) - Returns type

'b(result element type) - Might throw errors of type

'e

- Takes type

-> Array<'b>- returns array of transformed typethrows 'e- propagates errors from the transform function

Quick Reference Table

| Notation | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

'a, 'b, 'e | Type parameter (generic) | fn('a) -> 'a |

'_23, '_24, '_25 | Inferred type parameter (generic) | fn('_23) -> '_23 |

?#param | Optional labeled argument | fn(?#x: i64 = 0) |

#param | Required labeled argument | fn(#x: i64) |

@args | Variadic (any number of args) | fn(@args: i64) |

&T | Reference to type T | fn(&string) |

throws 'e | Can throw errors of type ’e | fn() -> i64 throws 'e |

[T, U] | T or U (set/union type) | [i64, null] |

-> | Returns | fn(i64) -> string |

Array<T> | Array of T | Array<string> |

Map<K, V> | Map with keys K, values V | Map<string, i64> |

Error<'e> | Error containing type ’e | Error<\ParseError>` |

Result<'r, 'e> | Success ’r or Error ’e | Result<i64, \Err>` |

Option<'a> | Value ’a or null | Option<string> |

Tips for Reading Signatures

- Start with the basics - identify parameters and return type

- Look for type parameters - they tell you about genericity

- Check for optional/labeled args - they indicate flexibility in calling

- Note reference types - important for reactivity

- Watch for throws - you’ll need error handling

- Don’t panic at complexity - break it down piece by piece

Remember: you don’t need to memorize these patterns. As you use Graphix, you’ll naturally become familiar with common signatures. This guide is here whenever you need a reminder!

See Also

- Fundamental Types - Built-in types and type sets

- Functions - Creating and using functions

- Error Handling - Working with errors and the throws system

- References - Deep dive into reference types

- User Defined Types - Structural typing and custom types

Let Binds

Let bindings introduce names that are visible in their scope after they are defined.

let x = 2 + 2 + x; // compile error x isn't defined yet

let y = x + 1 // ok

The same name can be used again in the same scope, it will shadow the previous value.

let x = 1;

let x = x + 1; // ok uses the previous definition

x == 2 // true

You can annotate the binding with a type, which will then be enforced at compile time. Sometimes this is necessary in order to help type inference.

let x: Number = 1; // note x will be of type Number even though it's an i64

let y: string = x + 1; // compile time type error

You can use patterns in let binds as long as they will always match.

let (x, y) = (3, "hello"); // binds x to 3 and y to "hello"

x == 3; // true

y == "hello" // true

You can mix type annotations with pattern matches

let (x, y): (i64, string) = (3, "hello")

You can assign documentation to a let bind using a /// comment. Documentation

will be displayed in the shell when the user tab completes and will be made

available by the lsp server.

// this is a normal comment

let x = 1;

/// this is documentation for y

let y = 2;

Connect

Connect, written x <- expr is where things get interesting in Graphix. The

sharp eyed may have noticed that up until now there was no way to introduce a

cycle in the graph. Connect is the only graph operator in Graphix, it allows you

to connect one part of the graph to another by name, causing the output of the

right side to flow to the name on the left side. Consider,

let x = "off"

x <- time::timer(duration:1.0s, false) ~ "on"

print(x)

This program will first print off, and after 1 second it will print on. Note

the ~ operator means, when the expression on the left updates return the

current value of the expression on the right (called the sample operator). The

graph we created looks like,

const("off") ────────────────> "x" ──────> print

▲

│

│

time::timer ──> sample

▲

│

│

const("on")

We can also build an infinite loop with connect. This won’t crash the program, and it won’t stop other parts of the program from being evaluated,

let x = 0;

x <- x + 1;

print(x)

This program will print all the i64s from 0 to MAX and then will wrap around. It will print numbers forever. You might notice, and you might wonder, why does it start from zero, shouldn’t it start from 1? After all we increment x BEFORE the print right? Well, no, not actually, it will start at 0, for the same reason this infinite loop won’t lock up the program or cause other expressions not to be evaluated. Graphix programs are evaluated in cycles, a batch of updates from the network, timers, and other IO is processed into a set of all events that happened “now”, then the parts of the program that care about those particular events are evaluated, and then the main loop goes back to waiting for events.

What connect does is it schedules an update to x for the next cycle, the

current cycle proceeds as normal to it’s conclusion as if the connect didn’t

happen yet, because it didn’t. In the above case the event loop would never

wait, because there is always work to do adding 1 to x, however it will still

check for other events every cycle.

When combined with other operations, specifically select, connect becomes a powerful general looping construct, and is the only way to write a loop in Graphix. A quick example,

let count = {

let x = 0;

select x {

n if n < 10 => x <- x + 1,

_ => never() // never() never updates

};

x

};

count

This program creates a bind count that will update with the values 0 to 10. If

you put it in a file test.gx and execute it using graphix test.gx it will

print 0 to 10 and then wait.

$ graphix test.gx

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Is Connect Mutation?

Connect causes let bound names to update, so it’s kind of mutation. Kind of. A

better way to think about it is that every let bound value is a pipe with

multiple producers and multiple consumers. Connect adds a new producer to the

pipe. The values being produced are immutable, an array [1, 2, 3] will always

and forever be [1, 2, 3], but a new array [1, 2, 3, 4] might be pushed into

the same pipe [1, 2, 3] came from, and that might make it appear that the

array changed. The difference is, if you captured the original [1, 2, 3] and

put it somewhere, a new [1, 2, 3, 4] arriving on the pipe can’t change the

original array.

Blocks

A block is a group of code between { and } that has it’s own scope, and

evaluates to the last value in the block. Expressions in a block are ;

separated, meaning every expression except the last one must end in a ; and

it is illegal for a block to have just one expression (it will not parse).

You can use blocks to hide intermediate variables from outer scopes, and to group code together in a logical way.

let important_thing = {

let x = 0;

let y = x + 1;

43 - y

};

x; // compile error, x isn't in scope

y; // compile error, y isn't in scope

important_thing

This program won’t compile because you can’t reference y and x from outside the block scope. Blocks are valid anywhere an expression is valid, and they are just expressions. They will become very important when we introduce lambda expressions.

Use

Use allows you to bring names in modules into your current scope so they can be used without prefixing.

net::subscribe(...); // call subscribe in the net module

use net;

subscribe(...) // same function

Use is valid anywhere expressions are valid

let list = {

use array;

map([1, 2, 3, 4, 5], |x| x * 2)

};

list

will print [2, 4, 6, 8, 10]

let list = {

use array;

map([1, 2, 3, 4, 5], |x| x * 2)

};

map(list, |x| x * 2)

will not compile, e.g.

$ graphix test.gx

Error: in file "test.gx"

Caused by:

at line: 5, column: 1 map not defined

Use shadows earlier declarations in it’s scope. Consider,

let map = |a, f| "hello you called map!";

let list = {

use array;

map([1, 2, 3, 4, 5], |x| x * 2)

};

(list, map(list, |x| x * 2))

prints

$ graphix test.gx

([2, 4, 6, 8, 10], "hello you called map!")

Select

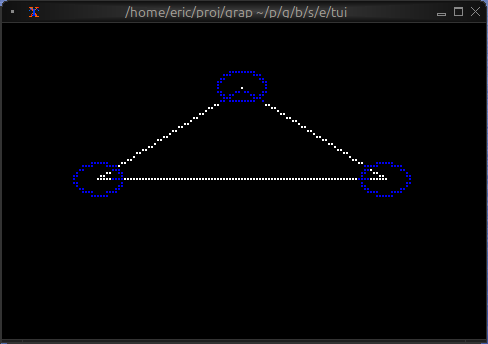

Select lets us create a graph node with multiple possible output paths that will choose one path for each value based on a set of conditions. Kind of like,

┌─────────────────────> if foo > 0 => ...

│

│

ref(foo) ──> select ─┼─────────────────────> if foo < 0 => ...

│

│

└─────────────────────> otherwise => ...

is written as

select foo {

n if n > 0 => ...,

n if n < 0 => ...,

n => ...

}

select takes an expression as an argument and then evaluates one or more “arms”. Each arm consists of an optional type predicate, a destructuring pattern, and an optional guard clause. If the type predicate matches, the pattern matches, and the guard evaluates to true then the arm is “selected”. Only one arm may be selected at a time, the arms are evaluated in lexical order, and first arm to be selected is chosen as the one and only selected arm.

The code on the right side of the selected arm is the only code that is evaluated by select, all other code is “asleep”, it will not be evaluated until it is selected (and if it has netidx subscriptions or published values they will be unsubscribed and unpublished until it is selected again).

Matching Types

Consider we want to select from a value of type [Array<i64>, i64, null],

let x: [Array<i64>, i64, null] = null;

x <- time::timer(duration:1.s, false) ~ [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

x <- time::timer(duration:2.s, false) ~ 7;

select x {

Array<i64> as a => array::fold(a, 0, |s, x| s + x),

i64 as n => n,

null as _ => 42

}

This program will print 42, 15, 7 and then wait. The compiler will check that you have handled all the possible cases. If we remove the null case from this select we will get a compile error.

$ graphix test.gx

Error: in file "test.gx"

Caused by:

missing match cases type mismatch [i64, Array<i64>] does not contain [[i64, null], Array<i64>]

If you read this carefully you can see that the compiler is building up a set of types that we did match, and checking that it contains the argument type. This goes both ways, a match case that could never match is also an error.

let x: [Array<i64>, i64, null] = null;

x <- time::timer(duration:1.s, false) ~ [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

x <- time::timer(duration:2.s, false) ~ 7;

select x {

Array<i64> as a => array::fold(a, 0, |s, x| s + x),

i64 as n => n,

f64 as n => cast<i64>(n)?,

null as _ => 42

}

Here we’ve added an f64 match case, but the argument type can never contain an

f64 so we will get a compile error.

$ graphix test.gx

Error: in file "test.gx"

Caused by:

pattern f64 will never match null, unused match cases

The diagnostic message gives you an insight into the compiler’s thinking. What

it is saying is that, by the time it’s gotten to looking at the f64 pattern,

the only type left in the argument that hasn’t already been matched is null,

and since f64 doesn’t unify with null it is sure this pattern can never

match.

Guarded patterns can always not match because of the guard, so they do not subtract from the argument type set. You are required to match without a guard at some point. No analysis is done to determine if your guard covers the entire range of a type.

let x: [Array<i64>, i64, null] = null;

x <- time::timer(duration:1.s, false) ~ [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

x <- time::timer(duration:2.s, false) ~ 7;

select x {

Array<i64> as a => array::fold(a, 0, |s, x| s + x),

i64 as n if n > 10 => n,

null as _ => 42

}

This will fail with a missing match case because the i64 pattern is guarded

and no unguarded pattern exists that matches i64.

$ graphix test.gx

Error: in file "test.gx"

Caused by:

missing match cases type mismatch [null, Array<i64>] does not contain [[i64, null], Array<i64>]

This is the same error you would get if you omitted the i64 match case

entirely.

Matching Structure

The type predicate is optional in a pattern, and the more commonly used pattern is structural. Graphix supports several kinds of structural matching,

- array slices

- tuples

- structs

- variants

- literals, ignore

NB: In most contexts you can match the entire value as well as parts of it’s

structure by adding a v@ pattern before the pattern. You will see this in many

of the examples.

Slice Patterns

Suppose we want to classify arrays that have at least two elements vs arrays that don’t, and we want to return a variant with a triple of the first two elements and the rest of the array or `Short with the whole array.

let a = [1, 2, 3, 4];

a <- [1];

a <- [5, 6];

select a {

[x, y, tl..] => `Ok((x, y, tl)),

a => `Short(a)

}

This program will print,

$ graphix test.gx

`Ok((1, 2, [3, 4]))

`Short([1])

`Ok((5, 6, []))

The following kinds of slice patterns are supported,

-

whole slice, with binds, or literals, e.g.

[1, x, 2, y]matches a 4 element array and binds it’s 2nd and 4th element toxandyrespectively. -

head pattern, like the above program, e.g.

[(x, y), ..]matches the first pair in an array of pairs and ignores the rest of the array, binding the pair elements toxandy. You can also name the remainder, as we saw, e.g.[(x, y), tl..]does the same thing, but binds the rest of the array totl -

tail pattern, just like the head pattern, but for the end of the array. e.g.

[hd.., {foo, bar}]matches the last element of an array of structs with fieldsfooandbar, bindinghdto the array minus the last element, andfooto field foo andbarto field bar.

Structure patterns (all of the different types) can be nested to any depth.

Tuple Patterns

Tuple patterns allow you to match tuples. Compared to slice patterns they are

fairly simple. You must specify every field of the tuple, you can choose to bind

it, or ignore it with _. e.g.

("I", "am", "a", "happy", "tuple", w, _, "patterns")

Struct Patterns

Struct patterns, like tuple patterns, are pretty simple.

{ x, y }if you like the field names then there is no need to change them{ x: x_coord, y: y_coord }but if you need to use a different name you can{ x, .. }you don’t have to write every field

Consider

let a = {x: 54, y: 23};

a <- {x: 21, y: 88};

a <- {x: 5, y: 42};

a <- {x: 23, y: 32};

select a {

{x, y: _} if (x < 10) || (x > 50) => `VWall,

{y, x: _} if (y < 10) || (y > 40) => `HWall,

{x, y} => `Ok(x, y)

}

does some 2d bounds checking, and will output

$ graphix test.gx

`VWall

`HWall

`VWall

`Ok(23, 32)

You might be tempted to replace y: _ with .. as it would be shorter.

Unfortunately this will confuse the type checker, because the Graphix type system

is structural saying {x, ..} without any other information could match ANY

struct with a field called x. This is currently too much for the type checker

to handle,

$ graphix test.gx

Error: in file "test.gx"

Caused by:

pattern {x: '_1040} will never match {x: i64, y: i64}, unused match cases

The error is slightly confusing at first, until you understand that since we

don’t know the type of {x, ..} we don’t think it will match the argument type,

and therefore the match case is unused. This actually saves us a lot of trouble

here, because the last match is exhaustive, if we didn’t check for unused match

cases this program would compile, but it wouldn’t work. You can easily fix this

by naming the type, and for larger structs it’s often worth it if you only need

a few fields.

type T = {x: i64, y: i64};

let a = {x: 54, y: 23};

a <- {x: 21, y: 88};

a <- {x: 5, y: 42};

a <- {x: 23, y: 32};

select a {

T as {x, ..} if (x < 10) || (x > 50) => `VWall,

T as {y, ..} if (y < 10) || (y > 40) => `HWall,

{x, y} => `Ok(x, y)

}

Here since we’ve included the type pattern T in our partial patterns the

program compiles and runs.

$ graphix test.gx

`VWall

`HWall

`VWall

`Ok(23, 32)

Note that we never told the compiler that a is of

type T. In fact T is just an alias for {x: i64, y: i64} which is the type

of a. We could in fact write our patterns without the alias,

{x: i64, y: i64} as {x, ..} if (x < 10) || (x > 50) => `VWall

The type alias just makes the code less verbose without changing the semantics.

Variant Patterns

Variant patterns match variants. Consider,

let v: [`Bare, `Arg(i64), `MoreArg(string, i64)] = `Bare;

v <- `Arg(42);

v <- `MoreArg("hello world", 42);

select v {

`Bare => "it's bare, no argument",

`Arg(i) => "it has an arg [i]",

x@ `MoreArg(s, n) => "it's big [x] with args \"[s]\" and [n]"

}

produces

$ graphix test.gx

"it's bare, no argument"

"it has an arg 42"

"it's big `MoreArg(\"hello world\", 42) with args \"hello world\" and 42"

Variant patterns enforce the same kinds of match case checking as all the other pattern types

let v: [`Bare, `Arg(i64), `MoreArg(string, i64)] = `Bare;

v <- `Arg(42);

v <- `MoreArg("hello world", 42);

select v {

`Bare => "it's bare, no argument",

`Arg(i) => "it has an arg [i]",

x@ `MoreArg(s, n) => "it's big [x] with args \"[s]\" and [n]",

`Wrong => "this won't compile"

}

yields

$ graphix test.gx

Error: in file "test.gx"

Caused by:

pattern `Wrong will never match [`Arg(i64), `MoreArg(string, i64)], unused match cases

Literals, Ignore

You can match literals as well as bind variables, as you may have noticed, and

the special pattern _ means match anything and don’t bind it to a variable.

Missing Features

A significant missing feature from patterns vs other languages is support for multiple alternative patterns in one arm. I plan to add this at some point.

Select and Connect

Using select and connect together is one way to iterate in Graphix. Consider,

let a = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

let len = 0;

select a {

[x, tl..] => {

len <- len + 1;

a <- tl

},

_ => len

}

produces

$ graphix test.gx

5

This is not normally how we would get the length of an array in Graphix, or even

how we would do something with every element of an array (see array::map and

array::fold), however it illustrates the power of select and connect together.

Error Handling

Errors in Graphix are represented by the Error<'a> type. A new instance of

which can be created with the error function. e.g.

〉error(`Foo)

-: Error<'a: `Foo>

error:"Foo"

Try Catch and ?

While errors are normal values, and can be matched in select, they can also be

thrown and handled like exceptions. The ? operator throws errors generated by

the expression on it’s left to the nearest try catch block in dynamic scope. for

example,

〉let a = [1, 2, 3, 4]

〉try a[15]? catch(e) => println(e)

-: i64

error:[["cause", null], ["error", ["ArrayIndexError", "array index out of bounds"]], ["ori", [["parent", null], ["source", "Unspecified"], ["text", "try a[15]? catch(e) => println(e)"]]], ["pos", [["column", i32:5], ["line", i32:1]]]]

Catches the array index error and prints it’s full context to stdout. Every

error raised with ? is wrapped in an ErrChain struct, the full definition of

which is,

type Pos = {

line: i32,

column: i32

};

type Source = [

`File(string),

`Netidx(string),

`Internal(string),

`Unspecified

];

type Ori = {

parent: [Ori, null],

source: Source,

text: string

};

type ErrChain<'a> = {

cause: [ErrChain<'a>, null],

error: 'a,

ori: Ori,

pos: Pos

}

This gives the full context of where the error happened, and whether it was previously caught and reraised, giving the full history back to the first time it was ever raised.

The scope is dynamic, not lexical, mirroring exception systems that unwind the stack,

〉let div0 = try |x| x / 0 catch(e) => println(e ~ "never triggered")

〉try div0(0) catch(e) => println(e)

-: i64

error:[["cause", null], ["error", ["ArithError", "attempt to divide by zero"]], ["ori", [["parent", null], ["source", "Unspecified"], ["text", "let div0 = try |x| x / 0 catch(e) => println(e ~ \"never triggered\")"]]], ["pos", [["column", i32:20], ["line", i32:1]]]]

The catch surrounding the function call site, not the definition site, is the one triggered.

Try Catch Block Value

The try catch block always evaluates to the last value inside the try catch, never to the value of the catch block. An error being raised to try catch does not stop the execution of nodes in the try catch.

Checked Errors

Graphix function types are annotated by the type of error they might raise. In

most cases this is automatic, but for some higher order functions it may be

necessary to specify it explicitly. For example array map has type

fn(Array<'a>, fn('a) -> 'b throws 'e) -> Array<'b> throws 'e indicating that

while the map function itself does not throw any errors, it will throw any

errors the function passed to it throws. This is all in the service of being

able to statically check the type of thrown errors, for example,

let a = [0, 1, 2, 3];

try a[0]? + a[1]?

catch(e) => select (e.0).error {

`ArithError(s) => println("arithmetic operation error [s]"),

`ArrayIndexError(s) => println("array index error [s]")

}

There are two types of errors that can happen in this example, and the compiler knows that. If you were to omit one of them, then the example would not compile. Suppose we remove the pattern for ArrayIndexError, we would get,

Error: in file "test.gx"

Caused by:

0: at: line: 3, column: 13, in: select (e.0).error {`ArithError(s) => ..

1: missing match cases type mismatch `ArithError('_1897: string) does not contain '_1895: [`ArithError(string), `ArrayIndexError(string)]

You’ll recognize that this is just the normal select exhaustiveness checking at work. Since errors are just normal types, the important point is the compiler knows the type of every error at compile time, everything else flows from there.

Unhandled Errors

By default when evaluating a file, the compiler will print a warning whenever an

error raised by ? is not handled explicitly by a try catch block. Arithmetic

errors such as overflow do not generate this warning by default. Using -W

flags you can change the compilers behavior in this respect.

The $ Operator, aka Or Never

The $ operator goes in the same position as ?, and is best described as “or

never”. If the expression on it’s left is a non error, then $ doesn’t do

anything, otherwise it logs the error at the warn! log level and returns

nothing. This is a concise way of writing,

select might_fail(1, 2, 3) {

error as _ => never(),

v => v

}

can instead be written as,

might_fail(1, 2, 3)$

The $ operator logs errors rather than silently discarding them, making it

easier to debug issues while still allowing execution to continue.

Functions

Functions are first class values. They can be stored in variables, in data structures, and they can be passed around to other functions. Etc. They are defined with the syntax,

|arg0, arg1, ...| body

This is often combined with a let bind to make a named function.

let f = |x, y| x + y + 1

f is now bound to the lambda that adds it’s two arguments and 1. You can also

use structure patterns in function arguments as long as the pattern will always

match.

let g =|(x, y), z| x + y + z

Type annotations can be used to constrain the argument types and the return type,

let g = |(x, y): (f64, f64), z: f64| -> f64 x + y + z

Functions are called with the following syntax.

f(1, 1)

Would return 3. If the function is stored in a data structure, then sometimes you need parenthesis to call it.

(s.f)(1, 1)

Would call the function f in the struct s.

Labeled and Optional Arguments

Functions can have labeled and also optional arguments. Labeled arguments need not be specified in order, and optional arguments don’t need to be specified at all. When declaring a function you must specify the labeled and optional arguments before any non labeled arguments.

let f = |#lbl1, #lbl2, arg| ...

In this case lbl1 and 2 are not optional, but are labeled. You can call f with

either labeled argument in either order. e.g. f(#lbl2, #lbl1, a).

let f = |#opt = null, a| ...

opt need not be specifed when f is called, if it isn’t specified then it

will be null. e.g. f(2) is a valid way to call f. You can also apply type

constraints to labeled and optional arguments.

let f = |#opt: [i64, null] = null, a| ..

Specifies that opt can be either an i64 or null and by default it is null.

The compiler implements subtyping for functions with optional arguments. For

example if you write a function that takes a function with a labeled argument

foo, you can pass any function that has a labeled argument foo, even if it

also has other optional arguments. The non optional and non labeled arguments

must match, of course. For example,

let f = |g: fn(#foo:i64, i64) -> i64, x: i64| g(#foo:x, x);

let g = |#foo:i64, #bar: i64 = 0, x: i64| foo + bar + x;

f(g, 42) // valid call

outputs

$ graphix test.gx

84

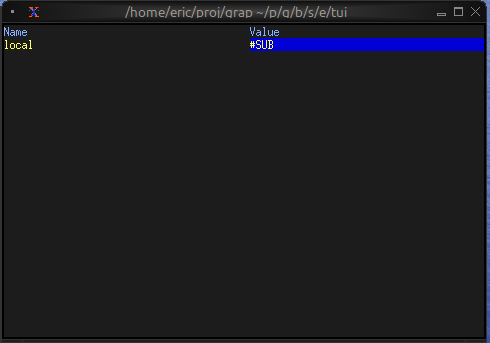

Lexical Closures

Functions can reference variables outside of their definition. These variables are captured by the function definition, and remain valid no matter where the closure is called. For example,

let f = {

let v = cast<i64>(net::subscribe("/local/foo")$)$;

|n| v + n

};

f(2)

f captures v and can use it even when it is called from a scope where v

isn’t visible. Closures allow functions to encapsulate data, just like an object

in OOP.

Functions are First Class values

We can store a function in a structure, which can itself be stored in a data structure, a file, or even sent across the network to another instance of the same program. Here we build a struct that maintains a count, and a function to operate on the count, returning a new struct of the same type with a different count.

type T = { count: i64, f: fn(T) -> T };

let t = { count: 0, f: |t: T| {t with count: t.count + 1} };

(t.f)(t)

when run this example will output,

{count: 1, f: 158}

158 is the lambda id, it’s the actual value that is stored to represent a function.

Late Binding

Functions are always late bound. Late binding means that the runtime actually

figures out which function is going to be called at runtime, not compile time.

At compile time we only know the type of the function we are going to call. This

complicates the compiler significantly, but it is a powerful abstraction tool.

For example we can create two structs of type T that each contain a different

implementation of f, and we can use them interchangibly with any function that

accepts a T. In this simple example we create one implementation of f that

increments the count, and one that decrements it.

type T = { count: i64, f: fn(T) -> T };

let ts: Array<T> = [

{ count: 0, f: |t: T| {t with count: t.count + 1} },

{ count: 0, f: |t: T| {t with count: t.count - 1} }

];

let t = array::iter(ts);

(t.f)(t)

when run this example will output,

{count: 1, f: 158}

{count: -1, f: 159}

You can clearly see that f is bound to different functions by the runtime since the lambda ids (158 and 159) are different. While Graphix is not an object oriented language, you can use closures and late binding to achieve some of the same outcomes as OOP.

Polymorphism

While the compiler does a pretty good job of inferring the types of functions, sometimes you want to express a constraint that can’t be inferred. Suppose we wanted to write a function that you can pass any type of number to, but it has to be the same type for both arguments, and the return type will be the same as the argument type. We can say that using type variables and constraints in our annotations.

〉let f = 'a: Number |x: 'a, y: 'a| -> 'a x + y

〉f

-: fn<'a: unbound: Number, '_2101: unbound: Error<ErrChain<`ArithError(string)>>>('a: unbound, 'a: unbound) -> 'a: unbound throws '_2101: unbound

160

In type annotations of lambda expressions,

- The constraints come before the first

|, separated by commas if there are multiple constrained type variables. e.g.'a: Number - Each argument may optionally have a

: Typeafter it, and this will set it’s type, e.g.x: 'a - After the second

|you can optionally include an-> Typewhich will set the return type of the function, e.g.-> 'a - After the return type, you can optionally specify a throws type,

throws Type, which will set the type that is thrown by the function

When a function type is printed, the stuff between the fn<> are the

type constraints, the syntax in this readout is a colon separated list

of,

- type variable name, for example ’_2073

- current value, or unbound if there is no current value

- constraint type

fn<'a: unbound: Number,

'_2101: unbound: Error<ErrChain<`ArithError(string)>>>

('a: unbound, 'a: unbound) -> 'a: unbound throws '_2101: unbound

We can remove the (unbound) current values and it becomes easier to read,

fn<'a: Number,

'_2101: Error<ErrChain<`ArithError(string)>>>

('a, 'a) -> 'a throws '_2101

We just have two variables now, 'a representing both argument types

and the return type, and '_2101 representing the throws type. We can

still call this f with any number type,

〉f(1.212, 2.0)

-: f64

3.2119999999999997

However notice that we get back the explicit type we passed in,

〉f(2, 2)

-: i64

4

In one case f64, in the other i64. We can’t pass numbers of

different types to the same call,

〉f(1, 1.2)

error: in expr

Caused by:

0: at: line: 1, column: 6, in: f64:1.2

1: type mismatch 'a: i64 does not contain f64

Here the compiler is saying that 'a is already initialized as i64 and i64

doesn’t unify with f64.

Higher Order Functions

Since functions are first class, they can take other functions as arguments, and even return functions. These relationships can be often inferred automatically without issue, but sometimes annotations are required.

〉 let apply = |x: 'a, f: fn('a) -> 'b throws 'e| -> 'b throws 'e f(x)

〉 apply

-: fn<'e: unbound: _>('a: unbound, fn('a: unbound) -> 'b: unbound throws 'e: unbound) -> 'b: unbound throws 'e: unbound

163

Here we’ve specified a single argument apply, it takes an argument, and a

function f, and calls f on the argument. Note that we’ve explicitly said

that whatever type of error f throws, apply will throw as well. That was

constrained by the compiler to _ meaning basically this could throw anything

or also not throw at all, it just depends on f.

We can see a more practical example in the type of array::map (this

implementation of which I will not repeat here), which is,

fn(Array<'a>, fn('a) -> 'b throws 'e) -> Array<'b> throws 'e

So map takes an array of 'a, and a function mapping 'a to 'b and possibly

throwing 'e and returns an array of 'b possibly throwing 'e.

Implicit Polymorphism

All functions are polymorphic, even without annotations, argument and return types are inferred at each call site, and thus may differ from one site to another. Any internal constraints are calculated when the definition is compiled and are enforced at each call site. For example consider,

〉let f = |x, y| x + y

〉f

-: fn<'_2073: unbound: Error<ErrChain<`ArithError(string)>>, '_2069: unbound: Number, '_2067: unbound: Number, '_2071: unbound: Number>('_2067: unbound, '_2069: unbound) -> '_2071: unbound throws '_2073: unbound

159

The type is a bit of a mouthfull, lets format it a bit so it’s easier to read.

fn<'_2073: unbound: Error<ErrChain<`ArithError(string)>>,

'_2069: unbound: Number,

'_2067: unbound: Number,

'_2071: unbound: Number>

('_2067: unbound, '_2069: unbound) -> '_2071: unbound throws '_2073: unbound

Removing the unbounds,

fn<'_2073: Error<ErrChain<`ArithError(string)>>,

'_2069: Number,

'_2067: Number,

'_2071: Number>

('_2067, '_2069) -> '_2071 throws '_2073

Here we can see that '_2067, '_2069, and '_2071 represent the two

arguments and the return type of the function. They are all unbound, meaning

that when the function is used they can have any type. They are also all

constrained to Number, and this will be enforced when the function is called,

it’s arguments must be numbers and it will return a number. We learned this

because internally the function uses +, which operates on numbers, this

constraint was then propagated to the otherwise free variables representing the

args and the return type.

So in plain English this says that the arguments to the function can by any type as long as it is a number, and the function will return some type which is a number. None of the three numbers need to be the same type of number.

Finally lets address throws '_2073. This states that the function may throw an

error, and if it does it’s type will be '_2073, which in this case is

constrained to be

Error<ErrChain<`ArithError(string)>>.

This is what happens in the case of overflow, underflow, and other arithmetic

errors. The throws clause of the type is used by the try catch(e) => ...

expression to compute the type of e, which is just the union of all the throws

types within the try catch.

We can indeed call f with different number types, and it works just fine,

〉f(1.0, 1)

-: Number

2

The type we get back really depends on the values we pass. For example,

〉f(1.1212, 1)

-: Number

2.1212

Wherever we use f the compiler will force us to handle every possible case in

the Number type

Recursion

Functions can be recursive, however there is currently no tail call optimization, so you can easily exhaust available stack space. With that warning aside, lets write a recursive function to add up pairs of numbers in an array,

let rec add_pairs = 'a: Number |a: Array<'a>| -> Array<'a> select a {

[e0, e1, tl..] => array::push_front(add_pairs(tl), e0 + e1),

a => a

}

running this we see,

〉add_pairs([1, 2, 3, 4, 5])

-: Array<'a: i64>

[3, 7, 5]

Detailed Semantics

Considering the underlying execution model functions might be better described as “polymorphic graph templates”, in that they allow you to specify a part of the graph once, and then use it multiple times with different types each time. Most of the time this difference in semantics doesn’t matter. Most of the time. Consider,

let f = |x, y| x + y + y;

let n = cast<i64>(net::subscribe("/hev/stats/power")?)?;

f(n, 1)

What happens here? Does f get “called” every time n updates? Does it only

work for the first n? Does it explode? Lets transform it like the compiler

would in order to understand it better,

let f = |x, y| x + y + y;

let n = cast<i64>(net::subscribe("/hev/stats/power")?)?;

n + 1 + 1

The “arguments” to the function call were plugged into the holes in the graph template and then the whole template is copied to the call site, and from then on the graph runs as normal.

So when n updates, the call site will return n + 2, since 1

never updates we don’t have to worry about it, however this same flow

applies when multiple arguments could update. In this case we’re just

having a philosophical discussion about how call sites are

implemented, however it DOES actually matter sometimes.

Where Function Semantics Matter

Lets revisit an earlier example where we used select and connect to find the length of an array. Suppose we want to generalize that into a function,

let len = |a: Array<'a>| {

let sum = 0;

select a {

[x, tl..] => {

sum <- sum + 1;

a <- tl

},

_ => sum

}

}

Here we have a function that takes an array with any element type and returns it’s length. Brilliant, lets call it,

let a = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

len(a)

and when we run this we get,

$ graphix test.gx

5

That’s the right answer. Are we done? Noooooooo. No we are not done. Lets see what happens if we do,

let a = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

a <- [1, 2, 3];

a <- [1, 2];

len(a)

this results in,

$ graphix test.gx

4

What!? That’s not even wrong. That’s just nonsense, what happened? The key to

understanding this problem is that there is just one call site, which means we

instantiated this little reusable bit of graph one time, just one time. That

means there is just one sum, one a, basically just one graph. When we use

connect to iterate we are using graph traversal cycles to do a new element of

the array every cycle until we are done. It will take 5 cycles for the first

array to be done, and that’s the problem, because we update a with a whole new

array in cycle 1 and again in cycle 2. That’s why we get 4, it’s determanistic,

we will get 4 every time.

- the first cycle we add 1 to

sumand set the inneratotl(it’s not the same variable as the outera, which is why the chaos isn’t even greater). But the outeraalso gets set to[1, 2, 3]and that overwrites the inner set because it happens after it (because that’s just the way the runtime works). - the second cycle we add 1 to

sumand set the innerato[2, 3]and the outerato[1, 2] - the third cycle we add 1 to

sumand set the innerato[2] - the 4th cycle we add 1 to

sumand setato[] - the 5th cycle we update our return value with

sum, which is now 4

We can only fix this be understanding that we’re programming a graph. I tried to

make Graphix as much like a normal language as possible, but this is where we

depart from that possibility. The general idea is, we need to queue updates to

the outer a until we’re done processing the current one. For that we have a

builtin called queue, here is the correct implementation

let len = |a: Array<'a>| {

let clock = once(null);

let q = queue(#clock, a);

let sum = 0;

select q {

[x, tl..] => {

sum <- sum + 1;

q <- tl

},

_ => {

clock <- null;

sum <- 0;

once(sum)

}

}

}

Every time clock updates queue will output something it has queued, or if it

has nothing queued it will store that the next thing that arrives can go out

immediatly. So the first a will immediatly pass through the queue, but

anything after that will be held. Then the normal select loop will run, except

it will look at q instead of a now, so that a can update without

disturbing it. When we get to the terminating case, we update for next cycle

clock with null and sum with 0 and we return once(sum). We return

once(sum) instead of just sum because removing something from the queue

takes one cycle, so it will be two cycles before we start on the next array, and

in the mean time the existing array will still be empty, meaning the second

select arm will still be selected, and sum is updating to 0 which we do not

want to return. If we run this with the same set of examples we will get the

correct answer,

$ graphix cycle_iter.gx

5

3

2

This comes up other places as well, for example whenever we have to deal with something that does IO, like calling an RPC, subscribing to values in netidx, etc.

User Defined Types

You can define your own data types in Graphix. This is useful for many tasks, such as enforcing interface invariants, and modeling data. As a data modeling language Graphix supports both structures, so called conjunctive types, where you are modeling data that always appears together, and variants, or so called disjunctive types, where a type can be one of many possible types drawn from a set. This contrasts with other languages, for example Python, which only support conjunctive types.

Structural Typing

In most languages types are dealt with by name, meaning that two structs with exactly the same fields are still different types if they have a different name. The obvious implication of this is that all types need to be given a name, and thus declared. Graphix works differently. Types in Graphix are structural, meaning that types that are structurally the same are the same type. In fact types in Graphix don’t formally have names, there can be aliases for a large type to cut down on verbosity, but an alias is always resolved to the structural type when type checking. Because of this you don’t need to declare types before using them.

Set Based Type System